I love this quote! Einstein knew this - he knew that if learning meant being able to state the facts that somebody else had worked out, there must be nothing new to learn and therefore, to learn something new meant that you need to be able to think beyond what you are being told - hence we have the Theory of Relativity.

Sometimes, we assume our students can't do the thinking on their own, so we do it for them. We give them a ceiling of expectation. We lower expectations so that students, and sometimes their teachers, feel like they are achieving. But since there’s no need or expectation to extend and grow, students learn to live comfortably below the ceiling. It doesn't seem too bad while they're in the classroom. The problem occurs when they leave your room, go elsewhere, and realise they haven't grown enough to reach the things the world expects them to be able to reach on their own. We often see this with students transitioning to senior years to complete the HSC. Students who are high achievers in junior years struggle to maintain high results at HSC level as the high bands require sustained High Order Thinking (HOT) that the ceilings we have built in their junior years may not have developed thoroughly. Our goal ought to be to remove these ceilings; but if we consistently set assessments and pose questions that have very clear and reachable endpoints, students are going to keep bumping their heads on the academic ceilings we have built above them.

All students need and deserve a challenge. The high achievers and gifted students are the ones who least consistently receive one. Many of the strategies AVID uses to engage students are designed to add that support when necessary. Most teachers feel comfortable and justified adding scaffolding to help modify or adapt the learning for those who struggle; however, many times we forget about the students on the other end of the spectrum. High achieving learners are wonderfully compliant and have learned that if they do what’s expected, they can rest comfortably for extended periods of time without having to exert much effort. Others become behaviour problems as they seek to entertain their idle brains!

Learning to think is a powerful tool. It allows you to understand the world around you, and to be critical, and have perspective, and develop empathy - all high order thinking objectives. It doesn’t happen easily. Henry Ford once stated “Whether you think you can or think you can’t - you’re right” and it is often this mindset that keeps students, and their teachers, from challenging themselves because they already think, or have been told, that they don’t need to do any better. Dr. Carol Dweck (psychologist), in her book Mindset (2006), states that changing the mindset of a student is the greatest way to encourage thinking. She believes that moving a student from a fixed mindset to a growth mindset has more to do with the teacher, and the environment they create within the classroom, than it does with the student. Dweck’s Mindset Theory suggests something as simple as “The Power of Yet” could change the way students see their abilities. This involves having students add the word ‘yet’ to the end of many statements we regularly hear in the classroom:

“I don’t get it … yet.”

“I can’t do this … yet.”

“This doesn’t work … yet.”

“I’m not good at English/Maths/Science … yet.”

Thinking hurts! It is hard work. It takes effort and time; both of which we do not always cater for in the classroom. We can be so busy giving students information that we can forgot to raise the ceiling by asking the questions that create a ‘thinking’ environment.

When students ask “How do I get an A in this assessment?” or “Can I get a Band 6 in this subject?”, we need to be ready and able to set them up for the challenge. When we look at the Common Grade Descriptors set by the BOSTES, we can identify the skills that are required to demonstrate a student's level of thinking. To get an ‘A’, a student needs to demonstrate their ability to readily apply extensive knowledge and skills in new situations - this requires the ability to think beyond the facts, push through the ceilings, question the information they are being given and create new meaning for the facts.

How do we develop High Order Thinking skills?

By making sure we remove any academic ceilings we have created and allow students to develop their thinking skills.

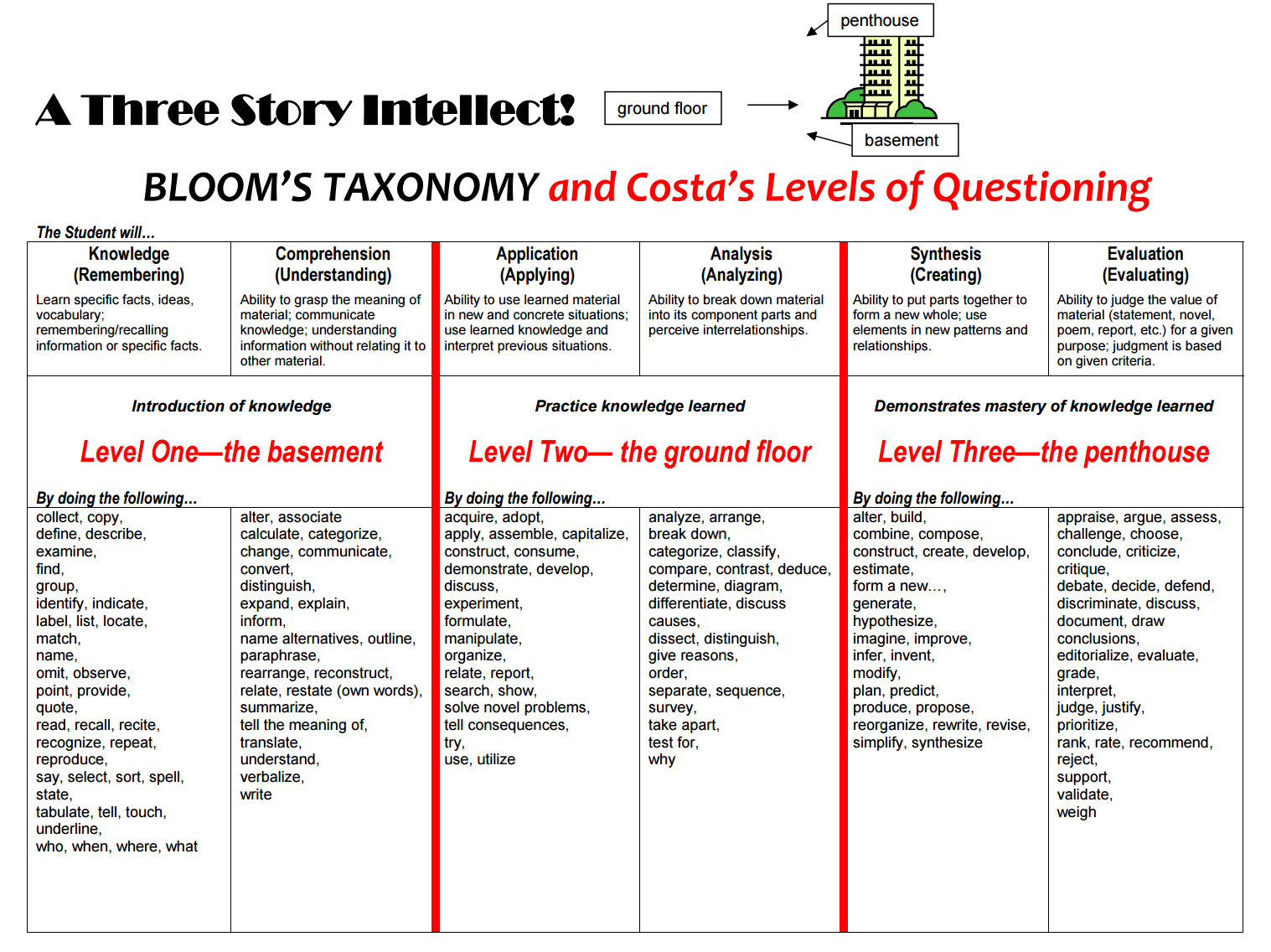

According the Dweck’s Mindset Theory, the brain is a muscle that needs to be trained. Students need to be given the opportunity to train their brain. Bloom’s Pyramid of Learning demonstrates levels that students can process though in order to ‘train their brain’. These levels of thinking and the various skills within the pyramid are required to become a High Order Thinker. The tasks and assessments we set ought to allow a student to think at a higher level than they thought they were capable of and, as teachers, we need to make sure that they understand the requirements of each level of thinking. This is what the Common Grade Descriptors are asking for and is required to move a student from a C to a B to an A.

For example, if a student completes a task where the skills only require them to remember and/or understand facts, then they are demonstrating skills at an adequate or satisfactory level, at the most. Even if they get 100% in the remember/understanding task, they have not demonstrated that they can think beyond the facts - they have not been required to apply, analyse, evaluate, create something out of the information they have learned. Importantly, they have not been given the opportunity to readily apply extensive knowledge and skills in a new situation.

These tasks may have some place within the learning process, but we need to ensure the students understand that their abilities are only being challenged at a low order thinking level. It may sound mean and I am in no way suggesting we put students down - I am a big believer in positive recognition; however, if we are not being honest with what we are asking students to achieve, we become engineers in building the ceilings that keep students at a certain learning level. Students will develop a ‘halo effect’ about their abilities. This halo effect tricks students, and sometimes teachers, into thinking they are achieving at a level higher than they actually are - I got 100% or an A, therefore I am clever at this. That required me to exert this kind of effort and that is all I have to do to be clever - and when we need them to push through the ceilings for the HSC, and they do not really know how or the amount of effort that is required - they have not 'trained their brain'.

How can we create lessons, tasks and assessments to promote Higher Order Thinking?

By considering the actions that are expected from the students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills and ensuring they are included within the instructions of the lesson, tasks and assessments.

Basically, what is it you are asking the students to do and how are you going to ask that? An AVID strategy used to ensure that a task promotes Higher Order Thinking is Questioning. Developing a strong question and breaking it down with students helps to understand what it is they are supposed to be learning. It can also work the other way; have students formulate their own questions and explain to you why they are asking that question.

In an AVID classroom each lesson starts with an essential question - it acts as a learning goal for the lesson. To develop an essential question, you need to consider what it is you want the student to know, practise and demonstrate during a lesson? AVID uses Costa’s Levels of Questioning to help develop thorough questions - it works at three levels of intellect and is often illustrated as a house.

Bloom’s Taxonomy works really well with Costa’s Levels of Questioning as demonstrated in the handout below. Use this handout as a scaffold for developing essential questions, class tasks and assessments. Spend some time examining the cognitive level of the questions and thinking in your classroom. Realising that some students will struggle to master the Level 1 knowledge and skills associated with your curriculum while others will catch on quickly, come to class prepared to challenge your kids at whatever level necessary. Level 2 and 3 of Costa’s Levels of Thinking requires students to make connections (within disciplines and among them), draw conclusions, predict, create, suppose, and evaluate. Providing increased opportunities to explore the curriculum at higher levels keeps the ceiling high above students’ heads.

High Order Thinking is essential for training students’ brain to think, altering mindsets and to make sure we are not constructing academic ceilings. Developing High Order Thinking activities within the classroom and through assessments will help to move students through the levels within the Common Core Descriptors. Above all, High Order Thinking is essential if we are to raise the expectations of the students themselves; helping them to realise, as Einstein did, “Education is not the learning of facts but the training of the mind to think”.